Net Zero & UK Inflation

Once again, the country is being sold a dangerous lie.

1 Background and General

Depending on your preferred measure, UK consumer price inflation is currently running at 10.1% or 8.9% (including owners’ housing costs), according to the latest update from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The fact that the headline item on this evening’s BBC news was about food price inflation illustrates the slowly growing awareness, even within our utterly discredited mainstream media organisations, that we have a bit of a serious problem on our hands.

In response to this “stickier than expected” inflation, the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee (BoE MPC) raised the UK base interest rate to 4.5% on 11th May. There have been hints that they may raise the rate again to 4.75%, or even 5%, in the coming months.

So what is going on, and why; will the BoE’s “strategy” work to control inflation and return it to their long-term target of 2%?

Typically, interest rate rises are used to control over-heating demand in an economy. The theory goes that accelerated consumer spending increases the demand for goods and services, reduces the unemployment rate, and tends to lead to higher prices, as there is less need for manufacturers and suppliers to aggressively compete for business. Companies make more money, employees demand higher salaries from a position of strength, and we enter into a “wage-price spiral”.

As prices rise, consumers are less keen to spend - especially on credit - so rising interest rates should dampen demand and bring inflation back under control.

However, there has been some debate, given the nature of the current inflation spike, whether rising interest rates will have the intended effect - and indeed whether they are at all necessary in the first place. The nature of today’s inflation, it is argued, is driven by “supply side” factors, not demand: In particular, the price of energy and food due primarily to the war in Ukraine. There is a risk that we enter a period of ‘stagflation’ as last seen in the 1970’s - a stagnating economy (a recession) with persistent high inflation.

There are five main components to the “cost of living crisis” currently afflicting the UK:

Money printing by the BoE during the Covid response - to pay for furlough, test & trace, vaccine costs, etc.

This came on top of the profligate money printing following the 2008 financial crisis, and pumped yet more additional money into the economy without being underpinned by any genuine economic activity, let alone growth.

At the same time, the BoE stubbornly held interest rates at historic low levels, when all the signs were there of an imminent inflationary surge.

This encouraged demand side inflation - especially from the affluent middle classes flush with furlough cash.

During the Covid restrictions, manufactures and suppliers were unable to fulfil the demand for many goods and services - for example, the supply of new cars largely dried up due to a shortage of electronic components from the far east. This was a supply side issue - the market demand for new (and used) cars was still there as restrictions were unwound, but the supply shortage meant an inflationary increase in prices.

Energy prices went through the roof, ostensibly because of a supply side issue with Russian gas.

Food prices have also increased dramatically, largely as a result of increased energy and fertiliser costs. A bodged implementation of Brexit may also have had some effect.

Again - food price increases represents supply side inflation.

As the BoE raises interest rates, the increased costs of mortgages (and rents) inflict additional pain on everyone except those who own their properties with no outstanding mortgage debt. This measure to “control inflation” actually increases real world inflation in the short term.

No unilateral mitigating measures in the UK could plausibly have done anything about item 2, since the crazed response to Covid was worldwide (though the UK played a full and active role in that).

Items 1 & 5 however are indisputably the direct result of government policy and/or official incompetence. Item 4 is largely a secondary effect of item 3 - energy prices - which was, and is, also a self-inflicted disaster of our own making.

2 Energy Costs (Domestic Consumers)

UK natural gas prices peaked last year at around 800 pence/therm, equivalent to 27p/kWh, but futures prices as of today (16th May 2023) are 75 pence/therm, or 2.6p/kWh, and falling.

During last winter, Ofgem’s energy price guarantee protected domestic consumers from some of the impact from the turmoil in wholesale markets. But prices are still very high and are causing real hardship to many people across the country.

Standing charges are non-trivial and have increased significantly in the last few years for reasons which, for the sake of brevity, I won’t go into in detail here. I will focus instead on unit costs, especially for electricity.

Ofgem provide a breakdown on their web site of a typical domestic electricity bill, as of August 2021 (when gas prices were not dissimilar to today).

As shown, wholesale costs comprise just under 30% of the total. For gas generation, the portion of this wholesale cost depends on the thermal efficiency of individual stations, as well as the operating costs (staff etc.) of each station. Modern CCGT stations can achieve an efficiency of up to 60% depending on age, how well optimised the output is and so on. Assuming an average of 50%, the proportion of your electricity bill from gas generation due to the fuel is about one seventh of the total. So, all other things being equal, you would expect a wholesale cost of 5.2p and an all-in retail price of around 18p/kWh from gas generation (12.8p of which is non-wholesale costs).

We have been told recently, by the likes of Caroline Lucas, that “offshore wind generation is 9 times cheaper than gas”. If the wholesale price of gas generation is 5.2p as above, that would imply a wind price of ~0.6p. Given that the amount of wind and gas generation were roughly equal during the first 3 months of 2023, we would expect an average wholesale price for both fuels of 2.9p and, adding 12.8p of other costs, an average retail price of around 15.7 pence.

So how can an average price of 34p/kWh be explained - disregarding the fact that standing charges have also increased massively?

The short answer is that Caroline Lucas and her eco-warrior peers constantly provide a wilfully misleading narrative about the relative costs of fossil fuel and renewable energy. Among many other sins, the “nine times cheaper” claim was timed to cherry pick data from the period of maximum gas prices.

The full answer, as ever, is a bit more complicated, but I will attempt to give a brief overview - without in any way intending to defend the situation.

20 years ago, most electricity was generated from ‘dispatchable’ fossil fuels (coal and gas) and nuclear, and was provided by the ‘Big Six’ suppliers left over from the privatisation of the industry - who were also significant generators, in a market (regulated by Ofgem) which very much favoured companies who were both generators and large suppliers.

Because of the nature of dispatchable generation, together with limited competition in the retail markets, the Big Six were able to ‘hedge’ their generation and wholesale positions by accurately predicting future retail demand, and ‘selling forward’ their generation, while ‘buying forward’ the gas and coal (and other input costs, including ‘carbon permits’) they’d need in advance. This kept prices relatively stable over the medium and long term, albeit that it meant genuine market competition was limited.

But two things changed dramatically over the past 15 years or so.

Firstly, smaller specialist suppliers were encouraged to enter the retail market (regulated by Ofgem). These suppliers were not necessarily backed by large generation portfolios - they were buyers only in the wholesale markets - and they did not generally establish such disciplined hedging processes as the Big Six. We’ve seen the results of this over the past couple of years as several of these new market entrants went bust as a direct result of massive exposure to wholesale price volatility. Taking risks is a rewarding tactic while conditions are in your favour, but not so good when things go dramatically wrong!

Customers of the failed providers have been transferred to other suppliers, who generally operate a more risk optimised hedging strategy. While providing better shelter from sudden wholesale market volatility, this also means that retail prices respond much more slowly to wholesale price changes - in both directions. Reductions in wholesale gas prices take a few months to begin to filter through to retail prices, and up to a couple of years to be fully reflected.

Put more simply, much of this year’s gas has already been bought at last year’s prices.

Secondly, the rapid growth in renewables generation, especially wind, has fundamentally changed how the wholesale markets are able to operate. Because wind is intermittent, it is impossible to know with any precision how much wind power will be generated on a specific day in, say, 6 months time. It is therefore much more difficult to predict overall gas generation - since gas generation is now expected to ‘take up the slack’ when the wind doesn’t blow. It also means that gas plants are often forced to operate at reduced thermal efficiency, but that’s another story.

In theory, ‘contract for difference’ (CfD) ‘strike prices’ are supposed to ensure a competitive market for renewable generation, but the Daily Sceptic has done a sterling job of exposing the incompetence (some might say blatant corruption) in the administration and policing of that system.

What this all means is that, in practice, wholesale power markets are heavily exposed to short term or spot prices in the wholesale gas markets. Gas producers - and wind generators - are gifted the opportunity to make a killing in such an environment, which is why the UK government introduced the Energy Profits Levy (EPL) on Jan 1st 2023 - essentially a 45% windfall tax on all electricity sold above a baseline £75 per MWh.

So how could (should) we minimise mid-term electricity prices, if we abandon the fiction that renewables are “cheap” and concentrated on urgently fixing the issues? In an ideal world, we certainly wouldn’t start from here, but here is where we unfortunately are.

Firstly, we need a centralised, coordinated view of our aggregate forward gas requirements, based on reasonable assumptions about average renewable availability, and the establishment of long-term gas contracts.

Secondly, we need to urgently revisit the contractual arrangements with wind generators. This is no doubt a legal minefield, but it needs to be addressed head on. We should not sanction the construction of a single additional MW of renewables until this issue is fully and transparently resolved.

I am now retired from the power industry, with no real-time intelligence of the situation in terms of progress with these first two items. Let us hope that there are a few sharp minds currently working on these challenges.

Thirdly, we should not in fact sanction the construction of a single additional MW of renewables, full stop. Abandoning the unachievable goal of Net Zero by 2050 would require the repeal of legislation which commits the government to do exactly that, so there is considerable urgency that we come to our national senses before the possibility of a Labour government, majority or minority, after the next election.

The entire economics of Net Zero is a flimsy house of cards built on a ragbag assortment of half-truths and lies, to solve a ‘problem’ which most genuine scientists and engineers believe is exaggerated or non-existent - and is in any case impossible to ‘solve’ without causing far more harm than good:

The Dummies Guide to UK Net Zero

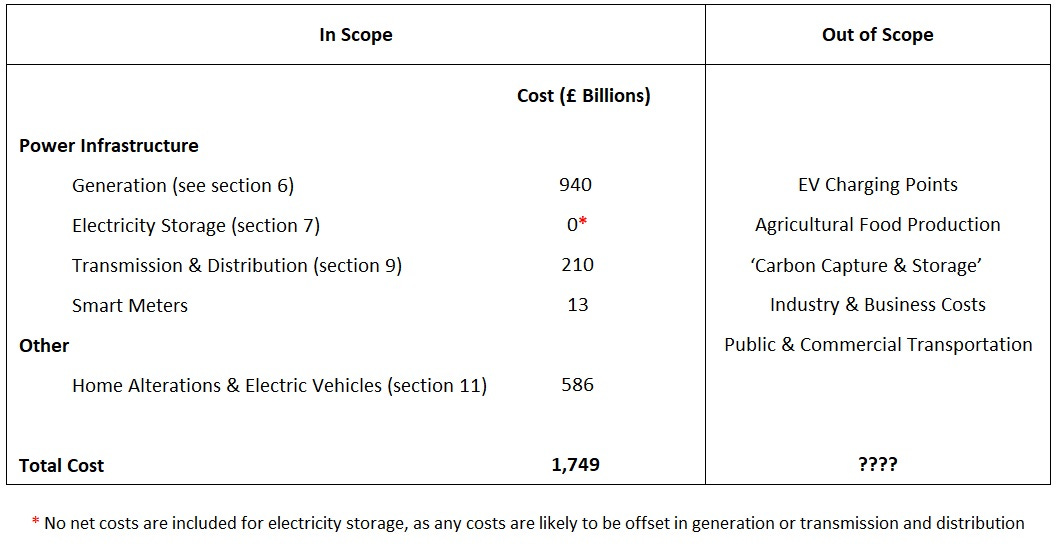

1. Executive Summary Whether by ignorance, malign intent, or a combination of both, the people of the world are being egregiously misled by the champions of the increasingly deranged Net Zero cult. We show that the cost of achieving Net Zero - if it were actually achievable in practice - would likely approach

Fourthly, the UK still has significant fossil fuel resources. We need to fall back in love with our own coal, gas and oil, and exploit them to the maximum of our technological capability. It is only a matter of fine margins and good luck (a mild European winter) that has saved us from the threat of widespread power cuts already - we may not be so lucky next year.

3 Conclusion

Current UK inflation is almost entirely the result of actions by our own government and administrative classes, going back at least two decades.

The biggest causative factor in the “cost of living crisis” is undoubtedly short term energy prices, which also impact most other consumer prices, including food - though increased borrowing costs (which have not yet fully filtered through to mortgage and rent costs) may well have an even bigger impact in the mid term.

We urgently need to address the lack of a coherent energy strategy and fix the broken wholesale energy market, to prevent our short term energy cost debacle from becoming permanent. To do that, we will need to acknowledge that there is a cabal of bad actors who want energy prices to remain high, in order to convince the masses that we need “cheap renewables” in order to fix a non-existent “climate crisis”.

Contrary to the official narrative (“it’s all Putin’s fault so we need to keep fighting an insane proxy war in Ukraine), it is actually the Covid madness and “war on climate change” (CO₂, N₂O from the use of nitrogen fertilisers, recent curtailments to red diesel entitlements and more) which has caused the vast majority of these problems.

Without energy and food price inflation, we wouldn’t need such high interest rates which only compound the pain. In fact, if we’d raised interest rates gradually 5 years ago, we might hardly have needed any additional increase at all now.

The Net Zero lunacy is not just something that will affect our children and grandchildren, 20 or 30 years down the line. It is happening now, and today’s inflation is the result. But this early economic harm is only the beginning. Social cohesion is already damaged following the crazed Covid response, industrial unrest is growing rapidly, and it may not be long at all before we see serious civil unrest.

On the other hand, properly exploiting our own fossil fuel resources, as well as rejuvenating our nuclear industry, would not only reverse the harm already done by the deranged Net Zero agenda, it would give the economy a massive economic and industrial boost which would see us thrive and prosper over the next few decades. It would be madness - an act of collective national insanity - to forego such an opportunity.

We really need to wake up and smell the coffee, before the damage is irreparable and the country is in flames.

Nice one John!